#toru kawai

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Underrated Godzilla suit actors.

They need more love!!!

Shinji Takagi

Isao Zushi

Toru Kawai (passed in 1996)

Mizuho Yoshida

#godzilla#suitmation#kaiju#godzilla suit actor#godzilla suit actors#shinji takagi#isao zushi#mizuho yoshida#toru kawai#gojira#suit actor#showa era#showa godzilla#millennium#millennium godzilla

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Films Watched in 2024: 31. メカゴジラの逆襲/Mekagojira no Gyakushū/Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975) - Dir. Ishirō Honda

#メカゴジラの逆襲#Mekagojira no Gyakushū#Terror of Mechagodzilla#Ishirō Honda#Katsuhiko Sasaki#Tomoko Ai#Akihiko Hirata#Katsumasa Uchida#Gorō Mutsumi#Toru Kawai#Ise Mori#Tatsumi Nikamoto#Godzilla#Mechagodzilla#Titanosaurus#Films Watched in 2024#My Edits#My Post

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

So not only did Toru Kawai (Godzilla in Zone Fighter & Terror of Mechagodzilla and Gamera in Gamera, Super Monster) play the Tyrannosaurus Rex in The Last Dinosaur, but he was also back in that suit to play Dinosaur Emperor Urulu in Great Dinosaur War: Aizenborg. But this does beg the question-- is that Kawai in the Tyrannosaurus suit dancing to Pink Lady’s U.F.O. in Urulu’s final episode (#19)? https://youtu.be/wGutIVBCxbY?t=7

#Toru Kawai#Godzilla#Gamera#Tsuburaya#The Last Dinosaur#Aizenborg#Izenborg#Ururu#Urulu#Pink Lady#UFO#The Attack of the Super Monsters#suitmation#things that make you go hmm

0 notes

Text

Hello everyone, today I wanna talk about the people behind DanPri characters (a.k.a. their VAs/seiyuu, though they do more than just voice act). Some kind of introduction I guess.

Sorry for reposting this, I accidentally posted it when I saved the draft :(

So without further ado, let's start! :D

Seiichirou Yamashita

Nicknames: Seichi (by Koba, Reiou), Sei-chan (by Tatsumaru), Yamashita-san/kun (by Kawai-kun, Uzawa-kun, almost everyone else) Birthday: May 21, 1992 Hometown: Hiroshima Agency: Office Osawa Some well-known roles outside PriPara: Touken Ranbu - Yagen Toushirou & Aizen Kunitoshi Horimiya - Toru Ishikawa Twisted Wonderland - Ace Trappola

Shougo's voice actor, the most normal one among WITH in a glance. His voice is generally low-to-mid tone, but he's also good at voicing mischievous early-teen boys. Seichi chose to be a voice actor because he's always loved acting, but he actually longed to be an actor. However, he sees voice acting as the most realistic path for him.

Seichi debuted from 2012, but it wasn't until 2016 that he started getting main roles. A year later, he got the role as Shougo. When he found out about PriPara stage play, where the main casts' VA also act on stage, he basically told the director that "If there's a stage play for DanPri too one day, I'm available (wink)". And yeah, that dream was no longer a dream, as he got to be Shougo's actor on the stage play.

Role in WITH: Tsukkomi (the "normal one")

If you watch them enough, you'd know that Kobatatsu and Reiou are known to be fooling around while Seichi reminds them to behave. He gets them to be back on track in radio shows, free talk sessions in lives, etc. However, according to Koba and Reiou, he's actually more carefree than it seems, and sometimes went out somewhere on his own without notice. In some fan reports, Seichi's often seen to be the one being doted on the most, and Koba-Reiou admitted through a Q&A session that he's the one that feels like the youngest despite being the tsukkomi.

Tatsuyuki Kobayashi

Nicknames: Kobatatsu (by fans/almost everyone), Ta-tan (by Seichi and other DanPri members), Tatsuyuki (by Seichi) Birthday: April 21, 1989 Hometown: Chiba Agency: avex Some well-known roles outside PriPara: King of Prism - Ace Ikebukuro Twisted Wonderland - Cater Diamond Paradox Live (Stage play) - Satsuki Ito

Asahi's voice actor, literal personification of bright morning sunshine on stage. He's actually more of a singer and stage actor than voice actor. He started his career as a singer after winning the 7th Anisong Grand Prix in 2013. You can see some footages of it on Youtube (here's the digest of his performances). After debuting as a singer, he also started acting on stage plays since 2016.

Kobatatsu's career as a voice actor started in 2015, and Asahi is his first non-nameless supporting role. His voice is generally mid-to-high, and he's good at playing cheerful, happy-go-lucky characters. Seichi said that Kobatatsu has a habit to talk in childish voice outside from work.

Role in WITH: Main performer + co-mentor(?)

Due to his background, he's the most experienced stage performer among WITH members. And because of that, he became the "main dancer" of WITH, especially during their early days. He also helped the other two on learning choreographies (e.g. Tick-Tock Magical Time for their first solo event) and on performing in general. Seichi and Reiou said that they learned a lot from him during the rehearsals of their stage play.

Reiou Tsuchida

Nickname: Tsuchi (by Tatsumaru), Reiou, Tsuchida-san Birthday: January 6, 1993 Hometown: Hokkaido Agency: 81produce Some well-known roles outside PriPara: Ensemble Stars - Tsukasa Suou VS AMBIVALENZ - Taiyo Haruno & Subaru Takaya

Koyoi's voice actor, one of the funniest guys in the industry. He started his career as voice actor in 2012, but he doesn't have that much leading roles yet. He has quite distinctive voice, but it's pretty versatile. Reiou started becoming more well-known after voicing in Ensemble Stars in 2015, and he got the role as Koyoi in 2017.

Although he seems so unserious, he's actually very multitalented. He's good at imitating other people's voice, drawing, making stories, singing, and so on. Reiou even drew WITH members on their birthday back in 2020 (here's the link: Shougo, Koyoi, Asahi). He started working on his own manga since 2023 and self-publishing it on his Twitter.

Role in WITH: Ghost-director

I've written about how Koyoi's past story was developed from Reiou's idea, but that's not the only thing he contributed to WITH's back story. He proposed many ideas for WITH Stage as they rehearsed, e.g. the dance battle scene between Koyoi and Shinya and DARKNESS SOUL duet scene with Shinya. The director originally asked him to do Koyoi's solo song on that part, but Reiou felt that it'd be more fitting to involve Shinya more.

He also came up with a concept for Quest Milky Way performance during their #IIZE Tour in 2019. Reiou asked the audience to light up their penlights in their own color instead of WITH's members, because WITH were going around the galaxy in that song, and the penlight colors represent everyone's colors as the "stars" (idols) in the galaxy.

Kentarou Kawai

Shinya's voice actor, a newcomer who debuted in 2019. He focuses more on being an actor than voice actor, so his only role as a seiyuu is Shinya so far. He's especially close with Uzawa-kun, often goes out together and even invited Uzawa-kun to his family's home. Some fans called the two of them "Tarotaro" (from Kentarou and Shoutarou).

Nickname: Ken-chan (by Seichi and other DanPri members), Kawataro (by some fans and DanPri members), Tono (by Uzawa-kun), Kawai-kun (by almost everyone) Birthday: April 7, 1997 Hometown: Tokyo Agency: Japan Music Entertainment

WITH members often praises Kawai-kun as a very earnest, polite, and hard-working kid. He's also a certified sword-fighting actor, and showcases his fighting skills through videos on his SNS accounts (example here). Among all DanPri casts, he's the one that often holds streaming to interact with fans via Instagram Live.

Shoutarou Uzawa

Nickname: Uzawa-kun (by almost everyone), Taroumaru (by fans) Birthday: January 22, 1997 Hometown: Chiba Agency: 81produce

Ushimitsu's voice actor, also a newcomer who works in the same company as Reiou. He has mid-to-high tone voice. He's voiced many supporting roles in anime, movie dub, and games. Before working under his current company, he was under Japan's children theater company.

Uzawa-kun is a Pretty Series fan, and he was really excited to get the role as Ushimitsu. He's also the one who played Adopara the longest (or, rather, the only one who really played it) among DanPri casts. He's really close with Kawai-kun, but due to the long stage play rehearsal, he used to call Kawai-kun "Tono" (Master) everywhere, even when they meet outside work.

Tatsumaru Tachibana

Nickname: Tatsumaru Birthday: April 21, 1991 Hometown: Fukui Prefecture Agency: Stay Luck Some well-known roles outside PriPara: The God of High School - Mori Jin Aoashi - Eisaku Ootomo Kabukicho Sherlock - Toratarou Kobayashi

Mario's voice actor, an experienced stage actor who started his career as a voice actor in 2019. His natural voice is mid-to-high and sounds mild. He started acting since the age of 10, joining his father's theater company and performing with traveling troupe. He became the theater company's chairman in 2010-2015 before deciding to reside in Tokyo and work there.

Like Kawai-kun, he's also a certified sword-fighting actor, in addition to specializing in playing as a female on stage. His career as a voice actor is still quite short compared to his acting experience, but he's been climbing up in popularity and started getting more main roles. Among all DanPri casts, he's the closest with Seichi due to having voiced as main characters in a series together.

Oh, and he also has a youtube channel, although it doesn't seem to be that active lately.

#danpri#pripara#idol land pripara#yamashita seiichirou#yamashita seiichiro#kobayashi tatsuyuki#tsuchida reiou#uzawa shoutarou#kawai kentarou#tachibana tatsumaru#with#dark nightmare#mario#trivia

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

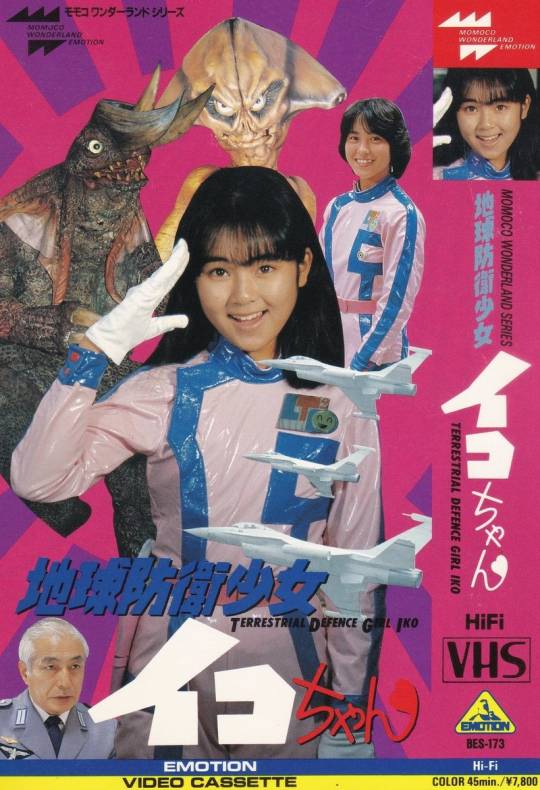

Chikyuu Bouei Shoujo Iko-chan

One of the interesting side effects of defining this blog's scope in the way that I have is that, for better or for worse, only focusing on magical girl manga that don't have anime adaptations automatically filters out almost every multimedia franchise. Sure we've talked about a couple manga adaptations of big live action productions, but there's a difference between that and a series that spreads itself across a handful of mediums simultaneously. Most magical girl multimedia projects from Japan will throw an anime of some form into the mix. Which is to say most, but not all. Today we'll be taking a look at a series which, throughout the late 80s and early 90s, released manga, a video game, a live action series, and more, but has no anime.

Chikyuu Bouei Shoujo Iko-chan (Terrestrial Defense Girl Iko) started as a live action direct-to-video series in 1987. The protagonist is Iko Kawai, a middle schooler who one day helps a member of the intergalactic police she sees lying unconscious on the pavement, and as a reward she is gifted a high tech headset called the Super Incom. The Super Incom allows her to use ESP to do what she believes is right, giving her abilities including but not limited to instant outfit changes, teleportation, leaping tall buildings in a single bound, shrinking, and communicating with beasts. In using her newfound powers, she catches the attention of an Earth defense squad known as the Light Terrestrial Defense Team, LTDT for short. They recruit Iko as a new member, and now armed with her Super Incom and gadgets from the LTDT, it is her duty to protect Earth from extraterrestrial threats.

The first entry in the series, an approximately 47 minute movie, was released on February 28, 1987. The monster designs were done by Toru Narita, who had done special effects work for Godzilla, and co-created Ultraman; so his involvement helped draw attention to the project. The series even has an Ultraman parody character in the form of Miracleman, who can grow to enormous size, but passes out when he does so.

A second movie was released on July 14, 1988, at the start of which Iko bequeaths her Super Incom to a new girl, coincidentally named Iko Sugekawa, who also goes on to work for the LTDT. While the original Iko was played by Akiko Isozaki, a relatively obscure child actress, the new Iko was played by Mia Masuda, a popular idol who was just getting her start around this time. This meant many Iko-chan fans were also Mia Masuda fans, and vice versa. Even now many people seem to know of the series predominantly through her involvement. This movie gives Iko a new (and more iconic) outfit, plus a spectacularly intelligent and accomplished rival named Runna Hakuba. Mia Masuda would stay on as Iko for the third movie, released on June 22, 1990, but each subsequent production would cast a different actress in the role. As for the series director, Minoru Kawasaki is known for producing tokusatsu parodies on the cheap, with Terrestrial Defense Girl Iko being one such example.

Due to the success of the original movie trilogy, a video game based on the series was released for the PC98 engine on December 4, 1992. Titled Chikyuu Bouei Shoujo Iko-chan ~UFO Daisakusen~ (Terrestrial Defense Girl Iko ~The Great UFO Strategy~, this is a turn-based battle game with visual novel elements, in which the LTDT face off against various aliens. Unfortunately, the game didn't sell well. It's speculated that the gameplay style didn't capture the appeal of the title's tokusatsu origins. The in-game art is very pretty though, for whatever that's worth.

Iko would continue starring in live action sequels and spinoffs after that, and a number of companion books were released for the series as well, but the release most relevant to this blog is the Iko-Chan manga.

Running in monthly Comic Comp from the May 1988 issue to the May 1991 issue, this manga was created by Yoshito Asari, with writing input from Minoru Kawasaki, the original director. Asari is best known for his involvement in the production of the original Evangelion anime, for which he was an assistant character designer, and he penned a 4koma spinoff titled Evangelion Yonkoma Zenshuu. However, he is an accomplished mangaka in his own right, creating works such as Wahhaman, Manga Science, and Space Family Carlvinson, the lattermost of which would get an OVA adaptation in 1988.

Over the course of its' run, the Iko-chan manga would amass a total of 32 chapters. The first tankobon volume, containing chapters 1 through 18, was published by Kadokawa on September 13, 1990, but the remainder of the series would not be compiled until a new edition of both volumes was released by Hakusensha under their Jets Comics label on December 25, 1999. A digital rerelease, also by Hakusensha, was made available on December 26, 2014.

This manga makes some changes to the original plot, particularly in Iko's backstory. In this version, Iko already works for the LTDT part-time at the start of the series, and she gets the Super Incom after helping Miracleman while he's drunk. It's less momentous, but I actually prefer it given how poorly the original Iko's buddying up to cops has aged. The way the Super Incom works is slightly different too: it activates when she says please, enunciating each syllable (o-ne-ga-i). This makes whatever she thinks will help happen, but if she attempts to use this power for selfish reasons, the device will malfunction.

Unfortunately, I wasn't able to read very much of the manga, and the language barrier made it difficult to get into any version of this series. Huge shout-out to the surprisingly detailed Japanese Wikipedia page, which was a tremendous help in researching for this overview. They also have quite a bit of information on later installments in this series I glossed over. There is a lot more I could get into, but I wanted to mainly focus on the meat of the franchise, and this post is long enough as is.

I really hope fan translations of the series become available one day, because Terrestrial Defense Girl Iko seems like a lot of fun, and I would definitely recommend it to fans of older tokusatsu. There are elements of it I don't vibe with, but still, it has an interesting premise, some decently entertaining humor, a super catchy theme song, and a killer aesthetic.

#my posts#long post#Chikyuu Bouei Shoujo Iko-chan#Terrestrial Defense Girl Iko#Earth Defense Girl Iko-chan#地球防衛少女イコちゃん#Minoru Kawasaki#河崎実#Yoshito Asari#Yoshitoh Asari#Yoshitoo Asari#あさりよしとお#Monthly Comic Comp#shounen#80s#live action#video game

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Terror of Mechagodzilla - Ishirō Honda 1975

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

their blushes are sure to both cure and kill me at the same time

#oikawa#oikawa toru#oikawa tooru#oikawa torū#haikyuu oikawa#haikyu#haikyuu#haikyuu!!#akaashi#akaashi keiji#keiji akaashi#haikyuu akaashi#uwu#toru oikawa#kawaii#kawai#kewt

123 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Promotional pictures of Allegiance Japanese production (2021)

March - April, 2021 | Tokyo / Nagoya / Osaka

濱田めぐみ Megumi Hamada (Kei Kimura) 海宝直人 Naoto Kaiho (Sammy Kimura) 中河内雅貴 Masataka Nakagauchi (Frankie Suzuki) 小南満佑子 Mayuko Kominami (Hannah Campbell) 上條恒彦 Tsunehiko Kamijo (Sam Kimura/Ojii-chan) 今井朋彦 Tomohiko Imai (Mike Masaoka) 渡辺徹 Toru Watanabe (Tatsuo Kimura)

照井裕隆 Hirotaka Terui, 西野誠 Nishino Makoto, 松原剛志 Tsuyoshi Matsubara, 俵和也 Kazuya Tawara, 村井成仁 Naruhito Murai, 大音智海 Tomomi Oto, 常川藍里 Airi Tsunekawa, 河合篤子 Atsuko Kawai, 彩橋みゆ Miyu Ayahashi, 小島亜莉沙 Arisa Kojima, 石井亜早実 Asami Ishii, 髙橋莉瑚 Rico Takahashi

Translation by 渋谷真紀子 Makiko Shibuya & 高橋知伽江 Chikae Takahashi Directed by Stafford Arima

#allegiance#allegiance musical#asiantheatrenet#george takei#stafford arima#japanese internment#musical theatre#japanese theatre#broadway#allegiancejp2021#japanesetheatre#picpost#newpost

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

♥︎。・゚♡゚・匚卄卂尺卂匚ㄒ乇尺丂 ㄥ|丂ㄒ・。♥︎。・゚

This is the character list only for bnha/mha, hxh, haikyu!!, and wonder egg priority.

Green means i’d love to write for that character and am likely to finish the request faster

Orange means it will take a bit longer either because i feel like i don’t know enough on that character to go as confidently as others or because i don’t enjoy it as much (i mainly write as something that i enjoy, not to make other people happy, though i love making other people happy :) )

Red means it’ll definitely take a while for that character and it could even take up to a month but i’ll likely just say no to the request if i think it’ll take that long

—— Aurelia <3

MY HERO ACADEMIA

MALE

• Izuku Midoriya

• Katsuki Bakugou

• Shouto Todoroki

• Denki Kaminari

• Hanta Sero

• Hitoshi Shinsou

• Tamaki Amajiki

• Mirio Togata

• Dabi/Touya Todoroki

• Tomura Shigaraki

• Shota Aizawa

• Keigo Takami

FEMALE

• Mina Ashido

• Kyouka Jirou

• Himiko Toga

HUNTER X HUNTER

MALE

• Hisoka Amorou

• Illumi Zoldyck

• Kurapika (NO NSFW)

• Killua Zoldyck (NO NSFW)

• Gon Freecss (NO NSFW)

HAIKYU!!

MALE (There will be more characters once i watch more of it dw)

• Tobio Kageyama

• Koshi Sugawara

• Kei Tsukishima

• Tadashi Yamaguchi

• Yuu Nishinoya

• Kenma Kozume

• Tetsurou Kuroo

• Koutarou Bokuto

• Keiji Akaashi

• Wakatoshi Ushijima

• Satori Tendou

• Toru Oikawa

• Kiyoomi Sakusa

WONDER EGG PRIORITY (NO NSFW)

FEMALE

• Ai Ohto

• Rika Kawai

• Neiru Aonuma

• Momoe Sawaki

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scary Music Masterpost

Season’s Creepings, all you lovely listeners; this is your DJ of darkness over at the Symphony of Death. Once again, it’s the time of year to update the Masterpost!Now you won’t find the classic Halloween haunts here, since those scares can be had anywhere, but maybe you’ll find a new favorite. Pull out your cauldron, brew up something nice, and kick back with me!

Masters of Horror

John Carpenter

Better Check the Kids - Halloween / Put Them in the Ground (with Jim Lang) - Body Bags / Main Theme - The Fog (1980) / All Out of Bubble Gum (with Alan Howarth) - They Live! / Hell Breaks Loose (with Alan Howarth) - Prince of Darkness / Regeneration - Christine / Just A Bedtime Story (with Jim Lang) - In the Mouth of Madness

Marco Beltrami

River’s Edge - My Soul to Take / Tea for Three Plus One - The Woman in Black / Return to Blackwood - Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark / The Concert - The Eye / Love Theme - Cursed / Priest Dies - Mimic / 1m2 (Production Note) - The Substitute / Return to Blackwood - Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark / Pulled Down Deep - The Shallows / The End of Fur - Cursed (II) / Carillon My Wayward Son - The Snowman

Charlie Clouser

American Horror Story Theme (with Cesar Davila-Irizarry) / Out of the Fire - The Collection /Hello, Zepp - Saw / Theme - Dead Silence

Bernard Herrmann

Teddy Bear Wired - Cape Fear / Theme - Vertigo / Theme - Psycho / The Tomb-Sandra - Obsession / Theme - Twisted Nerve / The Kidnapping - Obsession / Marketplace Murder - The Man Who Knew Too Much

Christopher Young

Twilight Mercy - Urban Legend / The Lament Configuration - Hellraiser / Sinister - Sinister /Concerto to Hell - Drag Me to Hell / The Devourer of Souls - Deliver Us from Evil / Butchers and Bakers - Copycat / Six Demons - The Exorcism of Emily Rose / Cryptomnesia - The Gift / The Sacrifice - The Dorm that Dripped Blood / Death After Life After Death - Untraceable / Reversing Colors - The Hider in the House / Church Isn’t Church - Pet Sematary (2019)

Video Games

Room of Angel - Akira Yamaoka & Mary Elizabeth McGlynn (Silent Hill: The Room) Mandus - Jessica Curry (Amnesia: A Machine For Pigs) The Drunken Whaler - Daniel Licht (Dishonored) Chill and Rigor - Shinji Hosoe (9 Persons 9 Hours 9 Doors) I’m Not Edible! - Chris Vrenna (American McGhee’s Alice) Ring Around the Rosie - Jason Graves (Dead Space 2) Soul of Steel - Mao Hamamoto (Corpse Party) P.T. Silent Hills Ambience Weekly Despair Magazine - Masafumi Takada (Dangan Ronpa) Close to Evil - Mikko Tarmia (Penumbra) In this Wretched Place - Eipix Studios (Phantasmat) The Nameless Game (Requiem) - Masayoshi Soken (Nanashi no Game) Last Day - Koji Kondo & Toru Minegishi (Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask) Welcome to Rapture - Garry Schyman (Bioshock) Theme - Yoan Landau (Nightmare House) Plague Blossom - Ndemic Creations (Plague Inc) Gore Nest - Mick Gordon (DOOM) Creepy Forest - Jason Garner & Vince Di Vera (Don’t Starve) A Nightmare Reborn - Ramin Djawadi (Gears of War) Before the Mirror - Maribeth Solomon & Brent Barkman (Fallen London) Broken Vessel - Christopher Larkin (Hollow Knight) Letter From A Friend - Carlos Viola (The Last Door) Rata Novus - Maclaine Diemer (Guild Wars 2: Heart of Thorns) The Hole at the Center of Everything - Alec Holowka (Night in the Woods) Bury Her - Ivan Zanotti (imscared) Devil’s Crossing - Steve Pardo (Grim Dawn)

Movies

Close to You (Carpenters Cover) - Josefine Cronholm (Mirrormask) The Void - Stephen Price (Gravity) Intro to Horror - Harry Manfredini (Friday the 13th) The Supper - Bruno Coulais (Coraline) Tubular Bells (Exorcist Cut) - Mike Oldfield (The Exorcist) Main Theme - Shiro Sato (Ju-On : The Grudge) Main Title - Wendy Carlos & Rachel Elkind (The Shining) Dark Earth - Jack Trombey (Dawn of the Dead) The Ringtone (Chakushin Ari) A New Swan Queen - Clint Mansell (Black Swan) Audition - Koji Endoh (Audition) Roar! - Michael Giacchino (Cloverfield) It Was Always You, Helen - Philip Glass (Candyman) Finale / End Titles - Howard Shore (Silence of the Lambs) A Discordant Split - Kenji Kawai (Ringu) Funeral in Carpathia - James Bernard (Dracula: Prince of Darkness) Name Your Poison - Christopher Lee (The Return of Captain Invincible) The Carousel After Dark - James Horner (Something Wicked This Way Comes) The Game Begins - Masamichi Amano (Battle Royale) The Event Horizon - Michael Kamen & Orbital (Event Horizon) Poison - Herman Kopp (Der Todesking) Samara’s Song - Daveigh Chase (The Ring) Brainerd, Minnesota - Carter Burwell (Fargo) Number One Fan - Marc Shaiman (Misery) Graveyard Theme - Vince Guaraldi (It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown) We are the 1% - Darren Baker (The Conspiracy) Call to Worship - Sons of Perdition (The Backwater Gospel) Longest Night - Thomas Newman (The Shawshank Redemption) The Auction - Michael Abels (Get Out)

Anime

Youran - Kayo Konishi & Yukio Konda (Elfen Lied) Aya - Mari Fukuhara (Amatsuki) I was waiting for this moment - Yuki Kajiura (Puella Magi Madoka Magica: Rebellion) Go DA DA - Yoko Kanno (Ghost in the Shell: SAC) A Last Flower - Asa-Chang & Junray (Aku no Hana) White Hill (Maromi’s Theme) - Susumu Hirasawa (Paranoia Agent) 24 Hours OPEN - Yoko Kanno (Cowboy Bebop) Nui Harime’s Theme - Hiroyuki Sawano (Kill La Kill) Daughter - Ichirou Imai & Kazuhisa Yamaguchi (Petshop of Horrors) Monster - Susumu Hirasawa (Berserk) Ake ni Somaru - Yasuharu Takanachi (Jigoku Shoujo) Sanctus - Hikaru Nanase (Angel Sanctuary) March of the Moving Dolls - Akira Senju (Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood)

Other

Stay Awake (Mary Poppins cover) - Suzanne Vega Heigh Ho (Snow White cover) - Tom Waits Come Little Children - Kate Covington I, Witchfinder - Electric Wizard Brennistein - Sigur Ros Psychobabble - Frou Frou Sirens - SingerSen Lose Your Soul - Dead Man’s Bones Grisly Reminder - Midnight Syndicate An Echo, A Stain - Bjork Elaine - ABBA (trust me) Welcome Home (Instrumental) - Coheed and Cambria The Greatest Show Unearthed - Creature Feature Something Wicked (That Way Went) - Vernian Process Black Water - Timber Timbre God’s Away on Business - Tom Waits The Wicked - Blues Saraceno The Gravedigger - The Pine Box Boys Lake Ponchartrain - Ludo The Smiler - IMA Score (Alton Towers Amusement Park) DOA - Bloodrock Breathing Water - Inhale Chupacabra Cha Cha - The Swingtips Confrontation - Anthony Warlow (Broadway’s Jekyll and Hyde) No Death - Mirel Wagner Thick as Thieves - Natalie Merchant Say Goodnight - Skeleton Key The Sad Mafioso - Godspeed You! Black Emperor What’s So Amazing About Grace? - The Paper Chase Blood on the Blue Grass - Legendary Shack Shakers In A Lonely Place - Joy Division Walpurgis - Black Sabbath

Television

Are You Afraid of the Dark? - Jeff Fisher Theme to Unsolved Mysteries - Michael Boyd & Gary Remal Malkin The Red Room - Angelo Badalamenti & David Lynch (Twin Peaks) Suite from “The Mark of the Rani” - Jonathan Gibbs (Doctor Who) Norma Doesn’t Approve - Chris Bacon (Bates Motel) The Cordyceps - George Fenton (Planet Earth) Dark Harvest Chase - Kevin Manthei (Invader Zim) Main Theme - Robert Lydecker & Brian Tyler (Sleepy Hollow) Blood Theme - Daniel Licht (Dexter) Arkham Asylum - Shirley Walker & Todd Hayen (Batman the Animated Series) The Old Mill - The Blasting Company (Over the Garden Wall) Sleep Deprivation - Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross (Bird Box) Turn on the Lights - Kyle Dixon & Michael Stein (Stranger Things)

149 notes

·

View notes

Photo

明日からはじまるグループ展のお知らせです。 @gallery_yamahon 箱類、染紙など豊富に納品しています。 お時間ございましたら、是非ご覧になってください。 VOL.131_Objects for Intentional Livings 生活工芸展 VI 会場1 史跡旧崇広堂 会期 2020年7月11日(土)〜7月26日(日) 開館時間 10:00〜18:00 休廊日 火曜 場所 史跡旧崇広堂(三重県伊賀市上野丸之内78-1) 会場2 gallery yamahon 会期 2020年7月11日(土)〜8月30日(日) 開館時間 11:00〜17:30 休館日 火曜 場所 gallery yamahon 出展作家 浅井庸佑/厚川文子/荒井智哉/安藤雅信/岩本忠美/岩田圭介/岩田美智子/内田鋼一/永木卓/大谷哲也/大谷桃子/大村剛/柏木円/加藤財/金森正起/川合優/寒川義雄/紀平佳丈/黒畑日佐代/小澄正雄/島田篤/城進/杉田明彦/��sen/竹口要/竹俣勇壱/辻村唯/津田清和/土田和茂/つちや織物所/富井貴志/冨沢恭子/中里隆/中野知昭/中村友美/中山秀斗/ハタノワタル/八田亨/初雪ポッケ/ヒガシ竹工所/ヒムカシ/福森道歩/古谷朱里/古谷宣幸/細川護光/細川由紀子/三谷龍二/山田洋次/山本忠正/吉田佳道/渡辺遼/atelier Une place surla Terre/Bowl Pond/mon Sakata/paisano オンライン展覧会 先行開催 ※初日は混雑が予想されるため、初日午前0時より[ yamahon online store ]でオンライン展覧会を開催いたします。 ご理解のほどよろしくお願い申し上げます。 【オンライン展覧会 生活工芸展】 GROUP EXHIBITION: Objects for Intentional Livings PLACE1: SUKODOU Jul. 11 - Jul. 26, 2020 Wednesday- Monday 10:00 - 18:00 Map: Sukodou PLACE2: gallery yamahon Jul. 11 - Aug. 30, 2020 Wednesday- Monday 11:00 - 17:30 Map: gallery yamahon Yosuke Asai, Fumiko Atsukawa, Tomoya Arai, Tadami Iwamoto, Keisuke Iwata, Michiko Iwata, Koichi Uchida, Taku Eiki, Tetsuya Otani Momoko Otani, Takeshi Omura, Madoka Kashiwagi, Takara Kato, Masaki Kanamori, Masaru Kawai, YoshioKangawa, Yoshitake Kihira, Hisayo Kurohata, Masao Kozui, Atsushi Shimada, Susumu Jo, Akihiko Sugita, Sen, Kaname Takeguchi, Yuichi Takemata, Yui Tsujimura, Kiyokazu Tsuda, Kazushige Tsuchida, Tsuchiya Textile Studio, Takashi Tomii, Kyoko Tomizawa, Takashi Nakazato, Tomoaki Nakano, Yumi Nakamura, Hideto Nakayama, Wataru Hatano, Toru Hatta, Hatsuyuki Pkke, Higashi Bamboo Studio, Himukashi, Michioh Fuumori, Akari Furutani, Noriyuki Furutani, Morimitsu Hosokawa, Yukiko Hosokawa, Ruji Mitani, Yoji Yamada, Tadamasa Yamamoto, Yoshimichi Yoshida, Ryo Watanabe, atelier Une place surla Terre, Bowl Pond, mon Sakata, paisano #ギャラリーやまほん #やまほん #生活工芸 #生活工芸展 #和紙 #和紙職人 #Japanesepaper #handmade #工芸 #支持体 #craft #art #ハタノワタル https://www.instagram.com/p/CCdArTEFEop/?igshid=1p3ntj446xmka

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Holy crap are we bad at having a schedule. But hey it’s a jumbo-sized episode just for you!!! Nothing less for the final flicks of the Showa era!!

Movies and their posters beneath the cut!

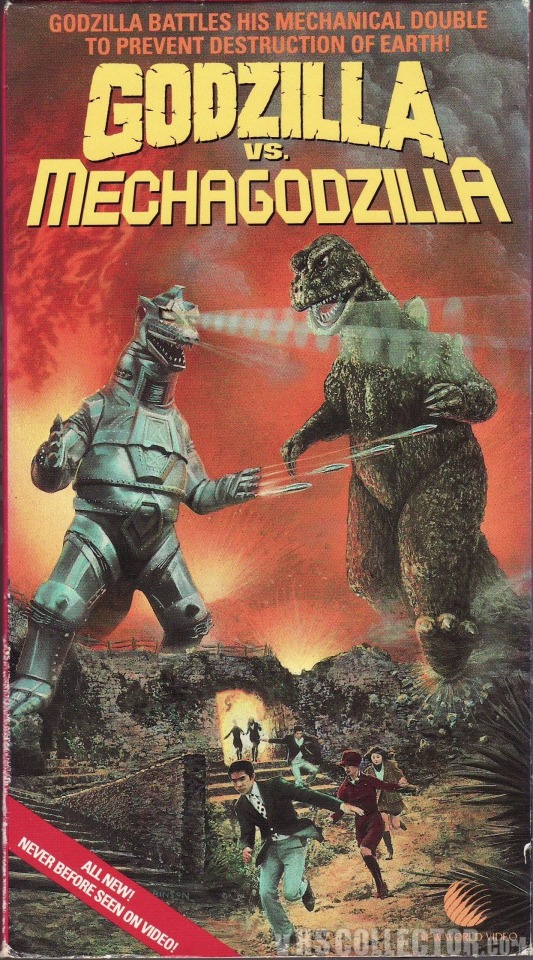

GODZILLA VS MECHAGODZILLA (1974)

Directed by Jun Fukuda Screenplay by Hiroyasu Yamamura and Jun Fukuda Story by Shinichi Sekizawa and Masami Fukushima Starring Masaaki Daimon, Kazuya Aoyama, Akihiko Hirata, and Hiroshi Koizumi Music by Masaru Sato Cinematography by Yuzuru Aizawa Edited by Michiko Ikeda

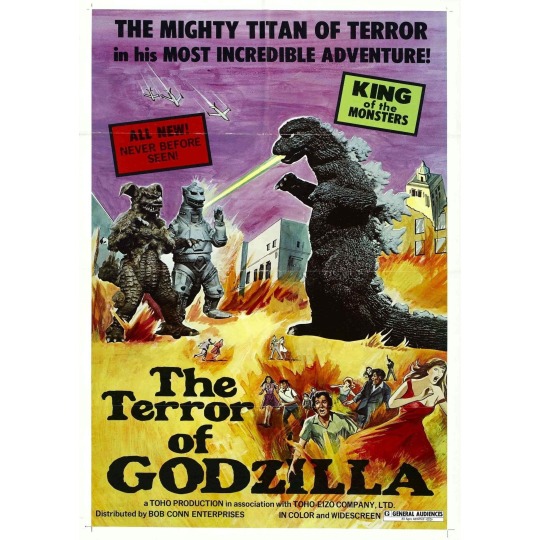

TERROR OF MECHAGODZILLA aka THE TERROR OF GODZILLA (1975)

Directed by Ishiro Honda Produced by Tomoyuki Tanaka and Henry G. Saperstein Written by Yukiko Takayama Starring Katsuhiko Sasaki, Tomoko Ai, Akihiko Hirata, Katsumasa Uchida, Goro Mutsumi, Tadao Nakamaru, and Toru Kawai Music by Akira Ifukube Cinematography by Sokei Tomioka Edited by Yoshitami Kuroiwa

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

GODZILLA wiki

Godzilla From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the monster. For the film franchise, see Godzilla (franchise). For other uses, see Godzilla (disambiguation). "ゴジラ" redirects here. For other uses of "Gojira", see Gojira (disambiguation). ‹ The template Infobox character is being considered for merging. › Godzilla Godzilla film series character Godzilla '54 design.jpg Godzilla as featured in the original 1954 film First appearance Godzilla (1954) Created by Tomoyuki Tanaka Ishirō Honda Eiji Tsubaraya Portrayed by Shōwa era: Haruo Nakajima[1] Katsumi Tezuka[2] Hiroshi Sekida[3] Seiji Onaka[3] Shinji Takagi[4] Isao Zushi[5] Toru Kawai[5] Hanna-Barbera: Ted Cassidy (vocal effects)[6][7] Heisei era: Kenpachiro Satsuma[8] Millennium era: Tsutomu Kitagawa[9] Mizuho Yoshida[10] Shin Godzilla: Mansai Nomura[11] TriStar Pictures: Kurt Carley[12] Frank Welker (vocal effects)[13] Legendary Pictures: T.J. Storm[14][15] Designed by Akira Watanabe Teizô Toshimitsu[16] Information Alias The King of the Monsters[17] Gigantis[18] Monster Zero-One[19] The God of Destruction[20][21] Species Prehistoric amphibious reptile Family Minilla and Godzilla Junior (adopted sons) Godzilla (Japanese: ゴジラ Hepburn: Gojira) (/ɡɒdˈzɪlə/; [ɡoꜜdʑiɾa] (About this soundlisten)) is a monster originating from a series of Japanese films of the same name. The character first appeared in Ishirō Honda's 1954 film Godzilla and became a worldwide pop culture icon, appearing in various media, including 32 films produced by Toho, three Hollywood films and numerous video games, novels, comic books and television shows. It is dubbed the King of the Monsters, a phrase first used in Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, the Americanized version of the original film.

Godzilla is depicted as an enormous, destructive, prehistoric sea monster awakened and empowered by nuclear radiation. With the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Lucky Dragon 5 incident still fresh in the Japanese consciousness, Godzilla was conceived as a metaphor for nuclear weapons.[22] As the film series expanded, some stories took on less serious undertones, portraying Godzilla as an antihero, or a lesser threat who defends humanity. With the end of the Cold War, several post-1984 Godzilla films shifted the character's portrayal to themes including Japan's forgetfulness over its imperial past,[23] natural disasters and the human condition.[24]

Godzilla has been featured alongside many supporting characters. It has faced human opponents such as the JSDF, or other monsters, including King Ghidorah, Gigan and Mechagodzilla. Godzilla sometimes has allies, such as Rodan, Mothra and Anguirus, and offspring, such as Minilla and Godzilla Junior. Godzilla has also fought characters from other franchises in crossover media, such as the RKO Pictures/Universal Studios movie monster King Kong and the Marvel Comics characters S.H.I.E.L.D.,[25] the Fantastic Four[26] and the Avengers.[27]

Contents 1 Overview 1.1 Name 1.2 Characteristics 1.3 Roar 1.4 Size 1.5 Special effects details 2 Appearances 3 Cultural impact 3.1 Cultural ambassador 4 References 4.1 Sources 5 External links Overview Name Gojira (ゴジラ) is a portmanteau of the Japanese words: gorira (ゴリラ, "gorilla") and kujira (鯨クジラ, "whale"), which is fitting because in one planning stage, Godzilla was described as "a cross between a gorilla and a whale",[28] alluding to its size, power and aquatic origin. One popular story is that "Gojira" was actually the nickname of a corpulent stagehand at Toho Studio.[29] Kimi Honda, the widow of the director, dismissed this in a 1998 BBC documentary devoted to Godzilla, "The backstage boys at Toho loved to joke around with tall stories".[30]

Godzilla's name was written in ateji as Gojira (呉爾羅), where the kanji are used for phonetic value and not for meaning.[citation needed] The Japanese pronunciation of the name is [ɡoꜜdʑiɾa] (About this soundlisten); the Anglicized form is /ɡɒdˈzɪlə/, with the first syllable pronounced like the word "god" and the rest rhyming with "gorilla". In the Hepburn romanization system, Godzilla's name is rendered as "Gojira", whereas in the Kunrei romanization system it is rendered as "Gozira".[citation needed]

During the development of the American version of Godzilla Raids Again (1955), Godzilla's name was changed to "Gigantis", a move initiated by producer Paul Schreibman, who wanted to create a character distinct from Godzilla.[31]

Characteristics

Every film incarnation of Godzilla between 1954 and 2017 Within the context of the Japanese films, Godzilla's exact origins vary, but it is generally depicted as an enormous, violent, prehistoric sea monster awakened and empowered by nuclear radiation.[32] Although the specific details of Godzilla's appearance have varied slightly over the years, the overall impression has remained consistent.[33] Inspired by the fictional Rhedosaurus created by animator Ray Harryhausen for the film The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms,[34] Godzilla's iconic character design was conceived as that of an amphibious reptilian monster based around the loose concept of a dinosaur[35] with an erect standing posture, scaly skin, an anthropomorphic torso with muscular arms, lobed bony plates along its back and tail, and a furrowed brow.[36] Art director Akira Watanabe combined attributes of a Tyrannosaurus, an Iguanodon, a Stegosaurus and an alligator[37] to form a sort of blended chimera, inspired by illustrations from an issue of Life magazine.[38] To emphasise the monster's relationship with the atomic bomb, its skin texture was inspired by the keloid scars seen on survivors in Hiroshima.[39] The basic design has a reptilian visage, a robust build, an upright posture, a long tail and three rows of serrated plates along the back. In the original film, the plates were added for purely aesthetic purposes, in order to further differentiate Godzilla from any other living or extinct creature. Godzilla is sometimes depicted as green in comics, cartoons and movie posters, but the costumes used in the movies were usually painted charcoal grey with bone-white dorsal plates up until the film Godzilla 2000.[40]

Godzilla's atomic heat beam, as shown in Godzilla (1954) Godzilla's signature weapon is its "atomic heat beam", nuclear energy that it generates inside of its body and unleashes from its jaws in the form of a blue or red radioactive beam.[41] Toho's special effects department has used various techniques to render the beam, from physical gas-powered flames[42] to hand-drawn or computer-generated fire. Godzilla is shown to possess immense physical strength and muscularity. Haruo Nakajima, the actor who played Godzilla in the original films, was a black belt in judo and used his expertise to choreograph the battle sequences.[43] Godzilla can breathe underwater[41] and is described in the original film by the character Dr. Yamane as a transitional form between a marine and a terrestrial reptile. Godzilla is shown to have great vitality: it is immune to conventional weaponry thanks to its rugged hide and ability to regenerate[44] and as a result of surviving a nuclear explosion, it cannot be destroyed by anything less powerful. Various films, television shows, comics and games have depicted Godzilla with additional powers, such as an atomic pulse,[45] magnetism,[46] precognition,[47] fireballs,[48] an electric bite,[49] superhuman speed,[50] eye beams[51] and even flight.[52]

Godzilla's allegiance and motivations have changed from film to film to suit the needs of the story. Although Godzilla does not like humans,[53] it will fight alongside humanity against common threats. However, it makes no special effort to protect human life or property[54] and will turn against its human allies on a whim. It is not motivated to attack by predatory instinct: it does not eat people[55] and instead sustains itself on nuclear radiation[56] and an omnivorous diet.[57] When inquired if Godzilla was "good or bad", producer Shogo Tomiyama likened it to a Shinto "God of Destruction" which lacks moral agency and cannot be held to human standards of good and evil. "He totally destroys everything and then there is a rebirth. Something new and fresh can begin."[55]

Godzilla battles King Kong in King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962). This film has the highest Japanese box office attendance figures in the entire Godzilla series to date.[58] In the original Japanese films, Godzilla and all the other monsters are referred to with gender-neutral pronouns equivalent to "it",[59] while in the English dubbed versions, Godzilla is explicitly described as a male, such as in the title of Godzilla, King of the Monsters!. The creature in the 1998 Godzilla film was depicted laying eggs through parthenogenesis.[60][61][62]

Roar Godzilla has a distinctive disyllabic roar (transcribed in several comics as Skreeeonk!),[63][64] which was created by composer Akira Ifukube, who produced the sound by rubbing a pine-tar-resin-coated glove along the string of a contrabass and then slowing down the playback.[65] In the American version of Godzilla Raids Again (1955) entitled Gigantis the Fire Monster, Godzilla's iconic roar was substituted with that of the monster Anguirus.[31] From The Return of Godzilla (1984) to Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991), Godzilla was given a deeper and more threatening-sounding roar than in previous films, though this change was reverted from Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992) onwards.[66] For the 2014 American film, sound editors Ethan Van der Ryn and Erik Aadahl refused to disclose the source of the sounds used for their Godzilla's roar.[65] Aadahl described the two syllables of the roar as representing two different emotional reactions, with the first expressing fury and the second conveying the character's soul.[67]

Size Godzilla's size is inconsistent, changing from film to film, and even from scene to scene, for the sake of artistic license.[55] The miniature sets and costumes were typically built at a 1⁄25–1⁄50 scale[68] and filmed at 240 frames per second to create the illusion of great size.[69] In the original 1954 film, Godzilla was scaled to be 50 m (164 ft) tall.[70] This was done so Godzilla could just peer over the largest buildings in Tokyo at the time.[2] In the 1956 American version, Godzilla is estimated to be 122 m (400 ft) tall, because producer Joseph E. Levine felt that 50 m did not sound "powerful enough".[71] As the series progressed Toho would rescale the character, eventually making Godzilla as tall as 100 m (328 ft).[72] This was done so that it would not be dwarfed by the newer, bigger buildings in Tokyo's skyline, such as the 243-meter-tall (797 ft) Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building which Godzilla destroyed in the film Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991). Supplementary information, such as character profiles, would also depict Godzilla as weighing between 20,000 and 60,000 metric tons (22,000 and 66,000 short tons).[70][72] In the American film Godzilla (2014) from Legendary Pictures, Godzilla was scaled to be 108.2 m (355 ft) and weighing 90,000 metric tons (99,000 short tons), making it the largest film version at that time.[73] Director Gareth Edwards wanted Godzilla "to be so big as to be seen from anywhere in the city, but not too big that he couldn't be obscured".[74] For Shin Godzilla (2016), Godzilla was made even taller than the Legendary version, at 118.5 m (389 ft).[75][76] In Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters, Godzilla's height was increased further still to 300 m (984 ft).[77]

Special effects details

Suit fitting on the set of Godzilla Raids Again (1955), with Haruo Nakajima portraying Godzilla on the left Godzilla's appearance has traditionally been portrayed in the films by an actor wearing a latex costume, though the character has also been rendered in animatronic, stop-motion and computer-generated form.[78][79]

Taking inspiration from King Kong, special effects artist Eiji Tsuburaya had initially wanted Godzilla to be portrayed via stop-motion, but prohibitive deadlines and a lack of experienced animators in Japan at the time made suitmation more practical. The first suit consisted of a body cavity made of thin wires and bamboo wrapped in chicken wire for support and covered in fabric and cushions, which were then coated in latex. The first suit was held together by small hooks on the back, though subsequent Godzilla suits incorporated a zipper. Its weight was in excess of 100 kg (220 lb).[40] Prior to 1984, most Godzilla suits were made from scratch, thus resulting in slight design changes in each film appearance.[80] The most notable changes during the 1960s-70s were the reduction in Godzilla's number of toes and the removal of the character's external ears and prominent fangs, features which would later be reincorporated in the Godzilla designs from The Return of Godzilla (1984) onward.[81] The most consistent Godzilla design was maintained from Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989) to Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995), when the suit was given a cat-like face and double rows of teeth.[82] Several suit actors had difficulties in performing as Godzilla, due to the suits' weight, lack of ventilation and diminished visibility.[40] Kenpachiro Satsuma in particular, who portrayed Godzilla from 1984 to 1995, described how the Godzilla suits he wore were even heavier and hotter than their predecessors because of the incorporation of animatronics.[83] Satsuma himself suffered numerous medical issues during his tenure, including oxygen deprivation, near-drowning, concussions, electric shocks and lacerations to the legs from the suits' steel wire reinforcements wearing through the rubber padding.[84] The ventilation problem was partially solved in the suit used in 1994's Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla, which was the first to include an air duct, which allowed suit actors to last longer during performances.[85] In The Return of Godzilla (1984), some scenes made use of a 16-foot high robotic Godzilla (dubbed the "Cybot Godzilla") for use in close-up shots of the creature's head. The Cybot Godzilla consisted of a hydraulically-powered mechanical endoskeleton covered in urethane skin containing 3,000 computer operated parts which permitted it to tilt its head and move its lips and arms.[86]

In Godzilla (1998), special effects artist Patrick Tatopoulos was instructed to redesign Godzilla as an incredibly fast runner.[87] At one point, it was planned to use motion capture from a human to create the movements of the computer-generated Godzilla, but it was said to have ended up looking too much like a man in a suit.[88] Tatopoulos subsequently reimagined the creature as a lean, digitigrade bipedal iguana-like creature that stood with its back and tail parallel to the ground, rendered via CGI.[89] Several scenes had the monster portrayed by stuntmen in suits. The suits were similar to those used in the Toho films, with the actors' heads being located in the monster's neck region, and the facial movements controlled via animatronics. However, because of the creature's horizontal posture, the stuntmen had to wear metal leg extenders, which allowed them to stand two meters (six feet) off the ground with their feet bent forward. The film's special effects crew also built a 1⁄6 scale animatronic Godzilla for close-up scenes, whose size outmatched that of Stan Winston's T. rex in Jurassic Park.[90] Kurt Carley performed the suitmation sequences for the adult Godzilla.[12]

In Godzilla (2014), the character was portrayed entirely via CGI. Godzilla's design in the reboot was intended to stay true to that of the original series, though the film's special effects team strove to make the monster "more dynamic than a guy in a big rubber suit."[91] To create a CG version of Godzilla, the Moving Picture Company (MPC) studied various animals such as bears, Komodo dragons, lizards, lions and gray wolves which helped the visual effects artists visualize Godzilla's body structure like that of its underlying bone, fat and muscle structure as well as the thickness and texture of its scale.[92] Motion capture was also used for some of Godzilla's movements. T.J. Storm provided the performance capture for Godzilla by wearing sensors in front of a green screen.[14]

In Shin Godzilla, a majority of the character was portrayed via CGI, with Mansai Nomura portraying Godzilla through motion capture.[11]

Appearances Main article: Godzilla (franchise) Further information: Godzilla (comics) Cultural impact Main article: Godzilla in popular culture

Godzilla's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame Godzilla is one of the most recognizable symbols of Japanese popular culture worldwide[93][94] and remains an important facet of Japanese films, embodying the kaiju subset of the tokusatsu genre. Godzilla's vaguely humanoid appearance and strained, lumbering movements endeared it to Japanese audiences, who could relate to Godzilla as a sympathetic character, despite its wrathful nature.[95] Audiences respond positively to the character because it acts out of rage and self-preservation and shows where science and technology can go wrong.[96]

In 1967, the Keukdong Entertainment Company of South Korea, with production assistance from Toei Company, produced Yongary, Monster from the Deep, a reptilian monster who invades South Korea to consume oil. The film and character has often been branded as a knock-off of Godzilla.[97][98]

Godzilla has been considered a filmographic metaphor for the United States, as well as an allegory of nuclear weapons in general. The earlier Godzilla films, especially the original, portrayed Godzilla as a frightening nuclear-spawned monster. Godzilla represented the fears that many Japanese held about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the possibility of recurrence.[99] As the series progressed, so did Godzilla, changing into a less destructive and more heroic character as the films became geared more towards children. Since then, the character has fallen somewhere in the middle, sometimes portrayed as a protector of the world from external threats and other times as a bringer of destruction.[100][101]

In 1996, Godzilla received the MTV Lifetime Achievement Award,[102] as well as being given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2004 to celebrate the premiere of the character's 50th anniversary film, Godzilla: Final Wars.[103] Godzilla's pop-cultural impact has led to the creation of numerous parodies and tributes, as seen in media such as Bambi Meets Godzilla, which was ranked as one of the "50 greatest cartoons",[104] two episodes of Mystery Science Theater 3000[105] and the song "Godzilla" by Blue Öyster Cult.[106] Godzilla has also been used in advertisements, such as in a commercial for Nike, where Godzilla lost an oversized one-on-one game of basketball to a giant version of NBA player Charles Barkley.[107] The commercial was subsequently adapted into a comic book illustrated by Jeff Butler.[108] Godzilla has also appeared in a commercial for Snickers candy bars, which served as an indirect promo for the 2014 movie. Godzilla's success inspired the creation of numerous other monster characters, such as Gamera,[109][110] Reptilicus of Denmark,[111] Yonggary of South Korea,[97] Pulgasari of North Korea,[112] Gorgo of the United Kingdom[113] and the Cloverfield monster of the United States.[114]

Godzilla's fame and saurian appearance has influenced the scientific community. Gojirasaurus is a dubious genus of coelophysid dinosaur, named by paleontologist and admitted Godzilla fan Kenneth Carpenter.[115] Dakosaurus is an extinct marine crocodile of the Jurassic Period, which researchers informally nicknamed "Godzilla".[116] Paleontologists have written tongue-in-cheek speculative articles about Godzilla's biology, with Ken Carpenter tentatively classifying it as a ceratosaur based on its skull shape, four-fingered hands and dorsal scutes, and paleontologist Darren Naish expressing skepticism while commenting on Godzilla's unusual morphology.[117]

Godzilla's ubiquity in pop-culture has led to the mistaken assumption that the character is in the public domain, resulting in litigation by Toho to protect their corporate asset from becoming a generic trademark. In April 2008, Subway depicted a giant monster in a commercial for their Five Dollar Footlong sandwich promotion. Toho filed a lawsuit against Subway for using the character without permission, demanding $150,000 in compensation.[118] In February 2011, Toho sued Honda for depicting a fire-breathing monster in a commercial for the Honda Odyssey. The monster was never mentioned by name, being seen briefly on a video screen inside the minivan.[119] The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society christened a vessel the MV Gojira. Its purpose is to target and harass Japanese whalers in defense of whales in the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary. The MV Gojira was renamed the MV Brigitte Bardot in May 2011, due to legal pressure from Toho.[120] Gojira is the name of a French death metal band, formerly known as Godzilla; legal problems forced the band to change their name.[121] In May 2015, Toho launched a lawsuit against Voltage Pictures over a planned picture starring Anne Hathaway. Promotional material released at the Cannes Film Festival used images of Godzilla.[122]

Steven Spielberg cited Godzilla as an inspiration for Jurassic Park (1993), specifically Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956), which he grew up watching.[123] Spielberg described Godzilla as "the most masterful of all the dinosaur movies because it made you believe it was really happening."[124] Godzilla also influenced the Spielberg film Jaws (1995).[125][126]

The main-belt asteroid 101781 Gojira, discovered by American astronomer Roy Tucker at the Goodricke-Pigott Observatory in 1999, was named in honor of the creature.[127] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 11 July 2018 (M.P.C. 110635).[128]

Cultural ambassador To encourage tourism in April 2015 the central Shinjuku ward of Tokyo named Godzilla an official cultural ambassador. During an unveiling of a giant Godzilla bust at Toho headquarters, Shinjuku mayor Kenichi Yoshizumi stated "Godzilla is a character that is the pride of Japan." The mayor extended a residency certificate to an actor in a rubber suit representing Godzilla, but as the suit's hands were not designed for grasping, it was accepted on Godzilla's behalf by a Toho executive. Reporters noted that Shinjuku ward has been flattened by Godzilla in three Toho movies.[129][130]

References Ryfle 1998, p. 178. Ryfle 1998, p. 27. Ryfle 1998, p. 142. Ryfle 1998, p. 360. Ryfle 1998, p. 361. Perlmutter 2018, p. 248. Morgan, Clay (March 23, 2015). "Ted Cassidy: The Man Behind Lurch, Gorn & TV's Incredible Hulk". Norvillerogers.com. Retrieved July 18, 2018. Ryfle 1998, p. 263. Kalat 2010, p. 232. Kalat 2010, p. 241. Ashcraft, Brian (August 1, 2016). "Meet Godzilla Resurgence's Motion Capture Actor". Kotaku. Retrieved August 1, 2016. Mirjahangir, Chris (November 7, 2014). "Nakajima and Carley: Godzilla's 1954 and 1998". Toho Kingdom. Retrieved April 5, 2015. Miller, Bob (April 1, 2000). "Frank Welker: Master of Many Voices". Animation World Network. Retrieved March 24, 2018. Arce, Sergio (May 29, 2014). "Conozca al actor que da vida a Godzilla, quien habló con crhoy.com". crhoy.com. Retrieved March 26, 2015. Pockross, Adam (February 28, 2019). "Genre MVP: The Motion Capture Actor Who's Played Groot, Godzilla, and Iron Man". Syfy Wire. Archived from the original on March 16, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019. "Making of the Godzilla Suit". Gojira - Classic Media 2006 Blu-ray/DVD Release. Retrieved April 6, 2018. Kalat 2010, p. 29. Solomon 2017, p. 32. Honda 1970, 21:57. Godzila, Mothra, and King Ghidorah (2001). Directed by Shusuke Kaneko. Toho DeSentis, John (July 4, 2010). "Godzilla Soundtrack Perfect Collection Box 6". SciFi Japan. Retrieved November 23, 2014. Brothers 2009. Barr 2016, p. 83. Robbie Collin (May 13, 2014). "Gareth Edwards interview: 'I wanted Godzilla to reflect the questions raised by Fukushima'". The Telegraph. Retrieved May 19, 2016. Godzilla, King of the Monsters (vol. 1) #1 (Marvel Comics, 1977) Godzilla, King of the Monsters (vol. 1) #20 (Marvel Comics, 1979) Godzilla, King of the Monsters (vol. 1) #23 (Marvel Comics, 1979) Ryfle 1998, p. 22. "Gojira Media". Godzila Gojimm. Toho Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2010. Ryfle 1998, p. 23. Ryfle 1998, p. 74. Peter Bradshaw (October 14, 2005). "Godzilla | Culture". London: The Guardian. Retrieved September 25, 2013. Biondi, R, "The Evolution of Godzilla – G-Suit Variations Throughout the Monster King's Twenty-One Films", G-Fan #16, July/August 1995 Greenberger, R. (2005). Meet Godzilla. Rosen Pub Group. p. 15. ISBN 1404202692 Kishikawa, O. (1994), Godzilla First, 1954 ~ 1955, Big Japanese Painting, ASIN B0014M3KJ6 Kravets, David (November 24, 2008). "Think Godzilla's Scary? Meet His Lawyers". Wired. Retrieved May 21, 2013. Snider, Mike (August 29, 2006). "Godzilla arouses atomic terror". USA Today. Retrieved May 30, 2013. Tsutsui 2003, p. 23. "Gojira". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved June 2, 2013. Making of the Godzilla Suit!. Ed Godziszewski. YouTube (December 24, 2010) An Anatomical Guide to Monsters, Shoji Otomo, 1967 "Interview with Haruo Nakajima". Godzilla - Criterion Collection 2012 Blu-ray/DVD Release. Missing or empty |url= (help); |access-date= requires |url= (help) The Art of Suit Acting - Classic Media Godzilla Raids Again DVD featurette Godzilla 2000 (1999). Directed by Takao Okawara. Toho. Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991). Directed by Kazuki Ōmori. Toho Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974). Directed by Jun Fukuda. Toho Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989). Directed by Kazuki Ōmori. Toho Godzilla: Destroy All Monsters Melee (2002). Pipeworks Software CR Godzilla Pachinko (2006). Newgin Zone Fighter (1973). Directed by Ishirō Honda et al. Toho The Godzilla Power Hour (1978). Directed by Ray Patterson and Carl Urbano. Hanna-Barbera Productions Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971). Directed by Yoshimitsu Banno. Toho Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964). Directed by Ishirō Honda. Toho. Godzilla: Unleashed - Godzilla 2000 character profile "Ryuhei Ktamura & Shogo Tomiyama interview - Godzilla Final Wars premiere - PennyBlood.com". Web.archive.org. February 3, 2005. Archived from the original on February 3, 2005. Retrieved September 25, 2013. The Return of Godzilla (1985). Directed by Koji Hashimoto. Toho Milliron, K. & Eggleton, B. (1998), Godzilla Likes to Roar!, Random House Books for Young Readers, ISBN 0679891250 Peter H. Brothers. Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda. Author House. 2009. Pgs. 47-48 Tsutsui 2003, p. 12. Ryfle 1998, p. 336. Kalat 2010, p. 225. Seibold, Witney (May 26, 2014). "Godzilla Goodness: Godzilla (1998)". Nerdist. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Stradley, R., Adams, A., et al. Godzilla: Age of Monsters (February 18, 1998), Dark Horse Comics; Gph edition. ISBN 1569712778 Various. Godzilla: Past Present Future (March 5, 1998), Dark Horse Comics; Gph edition. ISBN 1569712786 NPR Staff. "What's In A Roar? Crafting Godzilla's Iconic Sound". National Public Radio. Retrieved September 7, 2015. David Milner, "Takao Okawara Interview I", Kaiju Conversations (December 1993) Ray, Amber (May 22, 2014). "'Godzilla': The secrets behind the roar". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 19, 2016. "Godzilla". Gvsdestoroyah.dulcemichaelanya.com. Retrieved September 25, 2013. "Amazing and Interesting Facts about Godzilla Special Effects - Special Effects in Godzilla Movies - Hi-tech - Kids". Web Japan. Retrieved September 25, 2013. "Godzilla (1954) stats and bio page". www.tohokingdom.com. Retrieved March 8, 2013. Tsutsui 2003, p. 54-55. "Godzilla (1991) stats and bio page". www.tohokingdom.com. Retrieved June 3, 2015. "Godzilla Ultimate Trivia". The Movie Bit. Retrieved May 21, 2014. Owusu, Kwame (February 28, 2014). "The New Godzilla is 350 Feet Tall! Biggest Godzilla Ever!". MovieTribute. Retrieved February 20, 2018. "2016年新作『ゴジラ』 脚本・総監督:庵野秀明氏&監督:樋口真嗣氏からメッセージ". oricon.co.jp. Retrieved April 1, 2015. Ragone, August (December 9, 2015). "Japanese Press Reveals Shin Godzilla's Size". The Good, the Bad, and Godzilla. Retrieved February 20, 2018. Miska, Brad. "The Latest Godzilla is Three Times the Size of its Predecessors!". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved April 20, 2019. Failes, Ian (October 14, 2016). "The History of Godzilla Is the History of Special Effects". Inverse. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Ryūsuke, Hikawa (June 26, 2014). "Godzilla's Analog Mayhem and the Japanese Special Effects Tradition". Nippon.com. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Kalat 2010, p. 36. Kalat 2010, p. 160. Ryfle 1998, p. 254-257. Clements, J. (2010), Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade, A-Net Digital LLC, pp. 117-118, ISBN 0984593748 Kalat 2010, p. 258. Ryfle 1998, p. 298. Ryfle 1998, p. 232. Rickitt, Richard (2006). Designing Movie Creatures and Characters: Behind the Scenes With the Movie Masters. Focal Press. pp. 74–76. ISBN 0-240-80846-0. Rickitt, Richard (2000). Special Effects: The History and Technique. Billboard Books. p. 174. ISBN 0-8230-7733-0. "Godzilla Lives! - page 1". Theasc.com. Retrieved January 22, 2014. Ryfle 1998, p. 337-339. Dudek, Duane (November 8, 2013). "Oscar winner & Kenosha native Jim Rygiel gets UWM award". Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013. Carolyn Giardina (December 25, 2014). "Oscars: 'Interstellar,' 'Hobbit' Visual Effects Artists Reveal How They Did It". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 28, 2014. Sharp, Jasper (2011). Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780810857957. West, Mark (2008). The Japanification of Children's Popular Culture: From Godzilla to Miyazaki. Scarecrow Press. p. vii. ISBN 9780810851214. "Interview with Tadao Sato". Godzilla - Criterion Collection 2012 Blu-ray/DVD Release. Missing or empty |url= (help); |access-date= requires |url= (help) "The Psychological Appeal of Movie Monsters" (PDF). Calstatela.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 19, 2007. Retrieved September 28, 2013. Kalat 2010, p. 92. Demoss, David (June 18, 2010). "Yongary, Monster from the Deep". And You Thought It Was...Safe(?). Retrieved March 19, 2018. Rafferty, T., The Monster That Morphed Into a Metaphor, NYTimes (May 2, 2004) Lankes, Kevin (June 22, 2014). "Godzilla's Secret History". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Goldstein, Rich (May 18, 2014). "A Comprehensive History of Toho's Original Kaiju (and Atomic Allegory) Godzilla". Daily Beast. Retrieved March 19, 2018. "Godzilla Wins The MTV Lifetime Achievement Award In 1996 – Godzilla video". Fanpop. November 3, 1954. Retrieved April 13, 2010. "USATODAY.com - Godzilla gets Hollywood Walk of Fame star". Usatoday30.usatoday.com. November 30, 2004. Retrieved September 25, 2013. Beck, Jerry (ed.) (1994). The 50 Greatest Cartoons: As Selected by 1,000 Animation Professionals. Atlanta: Turner Publishing. ISBN 1-878685-49-X. "Godzilla Genealogy Bop" - MST3K season 2, episode 13, aired February 2, 1991 Song Review by Donald A. Guarisco. "Godzilla - Blue Öyster Cult | Listen, Appearances, Song Review". AllMusic. Retrieved September 25, 2013. Martha T. Moore. "Godzilla Meets Barkley on MTV". USA Today. September 9, 1992. 1.B. Paul Gravett and Peter Stanbury. Holy Sh*t! The World's Weirdest Comic Books. St. Martin's Press, 2008. 104. Kalat 2010, p. 23. Phipps, Keith (June 2, 2010). "Gamera: The Giant Monster". AV Club. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Don (June 16, 2015). "Reptilicus: Godzilla Goes To Denmark". Schlockmania. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Romano, Nick (April 6, 2015). "How Kim Jong Il Kidnapped a Director, Made a Godzilla Knockoff, and Created a Cult Hit". Vanity Fair. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Murray, Noel (May 8, 2014). "Meet Gorgo, the "British Godzilla"". The Dissolve. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Monetti, Sandro (January 13, 2008). "Cloverfield: Making of a monster". Express. Retrieved March 19, 2018. K. Carpenter, 1997, "A giant coelophysoid (Ceratosauria) theropod from the Upper Triassic of New Mexico, USA", Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 205 (#2): 189-208 Gasparini Z, Pol D, Spalletti LA. 2006. An unusual marine crocodyliform from the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary of Patagonia. Science 311: 70-73. Naish, Darren (November 1, 2010). "The science of Godzilla, 2010 – Tetrapod Zoology". Scienceblogs.com. Retrieved September 25, 2013. Toho sues Subway over unauthorized Godzilla ads, The Japan Times (April 18, 2008) Toho suing Honda over Godzilla, TokyoHive (February 12, 2011) "Sea Shepherd Conservation Society :: The Beast Transforms into a Beauty as Godzilla Becomes the Brigitte Bardot". Seashepherd.org. May 25, 2011. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2013. Gojira htm Biography and Band at the Gauntlet, The Gauntlet "Voltage Pictures Sued For Copyright Infringement". torrentfreak.com. Retrieved July 9, 2015. Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan's Favorite Mon-star: The Unauthorized Biography of "The Big G". ECW Press. p. 15. ISBN 9781550223484. Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan's Favorite Mon-star: The Unauthorized Biography of "The Big G". ECW Press. p. 17. ISBN 9781550223484. Freer, Ian (2001). The Complete Spielberg. Virgin Books. p. 48. ISBN 9780753505564. Derry, Charles (1977). Dark Dreams: A Psychological History of the Modern Horror Film. A. S. Barnes. p. 82. ISBN 9780498019159. "(101781) Gojira". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved July 19, 2018. "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved July 19, 2018. "Godzilla recruited as tourism ambassador for Tokyo". The Guardian. April 9, 2015. "Godzilla is Tokyo's newest resident and ambassador". New York Post. April 9, 2015. Sources Barr, Jason (2016). The Kaiju Film: A Critical Study of Cinema's Biggest Monsters. McFarland. ISBN 1476623953. Brothers, Peter H. (2009). Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda. CreateSpace Books. ISBN 1492790354. Edwards, Gareth (2014). Godzilla. Warner Bros. Pictures. Galbraith IV, Stuart (1998). Monsters Are Attacking Tokyo! The Incredible World of Japanese Fantasy Films. Feral House. ISBN 0922915474. Godziszewski, Ed (1994). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Godzilla. Daikaiju Enterprises. Honda, Ishiro (1970). Monster Zero (English version). Toho Co., Ltd/United Productions of America. Kalat, David (2010). A Critical History and Filmography of Toho's Godzilla Series (second edition). McFarland. ISBN 9780786447497. Lees, J.D.; Cerasini, Marc (1998). The Official Godzilla Compendium. Random House. ISBN 0-679-88822-5. Perlmutter, David (2018). The Encyclopedia of American Animated Television Shows. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 1538103737. Ragone, August (2007). Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-6078-9. Rhoads & McCorkle, Sean & Brooke (2018). Japan's Green Monsters: Environmental Commentary in Kaiju Cinema. McFarland. ISBN 9781476663906. Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan’s Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press. ISBN 1550223488. Ryfle, Steve; Godziszewski, Ed (2017). Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-7087-1. Solomon, Brian (2017). Godzilla FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the King of the Monsters. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. ISBN 9781495045684. Tsutsui, William M. (2003). Godzilla On My Mind: Fifty Years of the King of Monsters. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1403964742. External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to Godzilla. Wikiquote has quotations related to: Godzilla (franchise) Official website of Toho (Japanese) Godzilla on IMDb

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Toru Kawai off the shits

Godzilla goes HAM

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

TERROR OF MECHAGODZILLA (1975) – Episode 165 – Decades Of Horror 1970s

“They had their chance to learn about my ideas 15 years ago. *evil chuckle* Now they’ll pay for their scorn! I’ll exact vengeance upon those fools who treated me like a madman and drove me into the shadows! *maniacal laugh*” And with the help of his robotic daughter! Join your faithful Grue Crew – Doc Rotten, Chad Hunt, Bill Mulligan, and Jeff Mohr – as they go to Toho-land for Ishirô Honda’s Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975).

Decades of Horror 1970s Episode 165 – Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel! Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content! https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

Attempts to salvage Mechagodzilla are thwarted, causing an INTERPOL investigation that uncovers the work of a shunned biologist and his daughter, whose life becomes entwined with the resurrected machine.

Director: Ishirô Honda; Jun Fukuda (earlier film clips)

Writer: Yukiko Takayama

Selected cast:

Katsuhiko Sasaki as Akira Ichinose

Tomoko Ai as Katsura Mafune

Akihiko Hirata as Dr. Shinzo Mafune

Katsumasa Uchida as Jiro Murakoshi, Interpol Agent

Gorō Mutsumi as Mugal, Black Hole Alien leader

Toru Ibuki as Tsuda, Black Hole Alien lieutenant

Kenji Sahara as General Segawa

Tadao Nakamaru as Chief of Interpol Tagawa

Akinori Umezu as boy #1

Toru Kawai as Godzilla

Ise Mori as Mechagodzilla 2

Katsumi Nimiamoto as Titanosaurus

Terror of Mechagodzilla, aka Mekagojira no gyakushu, is Bill’s pick and even he is a bit surprised how little Godzilla is in the film. Even though Titanosaurus isn’t normally held in high regard, Bill thinks he’s a cool kaiju. Jeff is a relative newcomer to the world of Toho kaiju and he feels lucky to be shepherded through his introduction by the other members of the Grue-Crew. He gets into the campiness of Terror of Mechagodzilla, especially the fight scenes which seemed to him like a mashup of pro wrestling, boxing, and the Three Stooges. Chad loves all Godzilla films and sees him as emblematic of a good character that can be dropped into any situation – whether it be a comedy, child-oriented, or serious – and still tell a good story. He loves Terror of Mechagodzilla even though Godzilla does show up rather later in the story. Wacky aliens, a scientist that looks like Colonel Sanders, a robot daughter, and Godzilla appearing out of nowhere are all elements that pulled Doc into Terror of Mechagodzilla. He notes that even though this movie has a darker tone than recent Godzilla fare, it is still a lot of fun.

If you’re a fan of Godzilla, and we know you are, check out these other Decades of Horror podcasts on films from the Showa Era:

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974) – Episode 134 – Decades of Horror 1970s

Godzilla (Gojira, 1954) – Episode 58 – Decades of Horror: The Classic Era

Godzilla vs Hedorah (1971) – Episode 25 – Decades of Horror 1970s

At the time of this writing, Terror of Mechagodzilla is available to stream from HBOmax, the Criterion Channel, tubi, and various other streaming services. In terms of physical media, it is available in Godzilla: the Showa-Era Films, 1954–1975 (the Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray].

Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror 1970s is part of the Decades of Horror two-week rotation with The Classic Era and the 1980s. In two weeks, the next episode in their very flexible schedule, chosen by Chad, will be The Island of Dr. Moreau (1977) from the H.G. Wells novel, starring Burt Lancaster, Micahel York, Barbara Carrera, Nigel Davenport, and Richard Basehart.

We want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: leave us a message or leave a comment on the site or email the Decades of Horror 1970s podcast hosts at [email protected].

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Photo

Terror of Mechagodzilla - Ishirō Honda 1975

19 notes

·

View notes